Hello Dumpster Divers,

This took over a month to write and was almost lost forever this afternoon due to a nuclear Blogger blog-editing error in cross-contaminating the hard coding of the final notes for this post I had sketched down in LibreOffice while copying them to edit into the native Blogger blog editor.

Imagine taking a project of this size (one of the longest and most comprehensive posts I've written in a while), with no safety back up and with one foolish copy and paste into the blog and a one horrifyingly consequential back-keystroke (without reading the raw HTML), suddenly alter six weeks of work and research into an unreadable mess.

At least this time, it was merely altered. But it could be straightened out (if I recovered from my heart attack.) So I copied the entire post back into LibreOffice and line by line, replaced the paragraphs, photos and YouTube videos back in their proper order, editing and sweating bullets along the way.

Enjoy The Save,

Larry

|

|

1931 Crosley Roamio

(Image: Radiomuseum.org)

|

And talking to the passenger(s) in your car. And they weren't always pleasant to listen to.

Or singing/whistling/humming. Which made you unlistenable to the passengers in your car.

But by the 1920s, radio had just invaded the American home and people just couldn't get enough of it. Suddenly, the house wasn't so boring. But there were some major problems; The first radios were noisy, difficult to tune, needed tinny headsets or ugly sqwaky horns to listen to, required enormous outdoor antennas that few people then understood the science of and battery units with liquid acids that could leak and spill. And some people thought it was a dangerous distraction to have a radio in the car. And at that time, it really was.

But that didn't stop people from trying. There were attempts to bring radio to automobiles as early as 1904 when radio pioneer Lee DeForest demonstrated radio as a means of vehicle to vehicle communications at the 1904 World Exhibition in St. Louis.

|

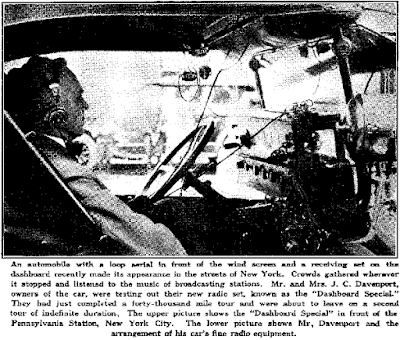

The October 28, 1922

issue of Radio World featured an early car radio prototype called

"The Dashboard Special"

|

But for the most part, car radios were still a rarity. A toy for the wealthy or those geeky enough to do it themselves. A lot of people still didn't even have home radios.

But before the invention of superheterodyne tuning,

radios in cars really weren't practical because the tuning of these

radios needed constant adjustment. So you also had to be very patient

and careful. The tuned radio frequency (TRF) receivers of that time

had three knobs just for tuning alone. And each had to be adjusted

individually for each radio frequency, which were of course, all AM.

|

A TRF radio from 1924.

You had to not only tune all three knobs to get on a specific

frequency, you also had to write down the number of each dial if you

wanted to tune back in to a specific station later. Image: Radio

Boulevard

|

Vibrations from the vehicle would also cause the

tuning to drift into an unlistenable mess after all your patience in

getting it tuned right. And secondly, there were no speakers. All

listening was done with headsets on these early car radios. Radios

were also prone to ghastly static interference from ignitions and

spark plugs.

Superheterodyne tuning was becoming standard on home receivers by the late 1920s. It reduced the tuning to a single knob and improved the sound, reception and stability of radios and once again, the idea of a radio just for cars was revisited. This time, it stuck.

In 1926, Philco invented what could be considered the very first mass produced car radio, the Transitone and production began for the 1927 model year to be an option in Chevrolet sedans.

Superheterodyne tuning was becoming standard on home receivers by the late 1920s. It reduced the tuning to a single knob and improved the sound, reception and stability of radios and once again, the idea of a radio just for cars was revisited. This time, it stuck.

In 1926, Philco invented what could be considered the very first mass produced car radio, the Transitone and production began for the 1927 model year to be an option in Chevrolet sedans.

Philco may have been first, but it was a man named

Paul Galvin that made the car radio a necessity. Galvin and his brother, Joseph, bought the bankrupt

Stewart Battery Company at auction for $750.

The Stewart Battery Company also offered The Battery

Eliminator, which allowed battery operated home radios to run on

household current, the forerunner to today's wall-wart AC adapters.

Which was also probably the likely cause of the Stewart Battery

Company's bankruptcy as well.

|

The Stewart Battery

Eliminator Model B. Image: This

Day In Tech History

|

The Galvin brothers were savvier than that. They

bought the Stewart Battery Company specifically for their

battery eliminator designs and manufacturing equipment for them. They

renamed as Galvin Manufacturing Corporation, ceased battery

production and concentrated only on battery eliminators for radios.

They had $565 in capital and five employees. The first week's payroll

was $63.

But battery eliminators themselves were becoming

obsolete as AC powered radios were becoming standard and the Galvin

brothers needed something fast. Paul Galvin had met two radio

engineers, William Lear and Elmer Wavering who created their own car

radio and demonstrated it at a radio convention in Chicago.

What made Lear and Wavering's design different was they also eliminated the static interference problem. They identified each cause of interference and created shielding to isolate it. With curiosity peaked, Paul Galvin set forth to create an easy to install, inexpensive car radio for the masses. His team built a working unit in Paul Galvin's Studebaker.

What made Lear and Wavering's design different was they also eliminated the static interference problem. They identified each cause of interference and created shielding to isolate it. With curiosity peaked, Paul Galvin set forth to create an easy to install, inexpensive car radio for the masses. His team built a working unit in Paul Galvin's Studebaker.

Galvin was so sure he hit solid gold that when he

applied for a business loan, he tried to clinch the deal by having

Lear and Wavering install a radio in the banker's car. The banker's

car caught fire a half hour later.

They didn't get the loan.

Unfazed, Galvin drove 800 miles to the Radio

Manufacturer's Association meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey in

June of 1930. Too broke to afford a booth, Paul Galvin just parked

outside the convention, turned up the volume for passersby to hear

and let his product speak for itself.

|

|

A reproduction of the

1930 Motorola ST71. The world's first after-market car radio. The

main chassis was bolted to the floor, the tuning and volume were made

to fit on the side of the steering column and the speaker was either

hung from the roof or placed haphazardly.on the floor. Sounds like my

old car. Image: MIT

Technology Review

|

And there were orders. Lots of them. And Galvin

Manufacturing Corporation was saved. But this radio needed a name.

And a "Galvin" just didn't seem very catchy. But Paul

Galvin came up with "Motorola", a play on "motor"

and "Victrola". There were lots of product names ending in

-ola. Movieola, Crayola. It just sounded good.

Galvin officially

renamed the company Motorola Inc in 1947. And an empire was born.

Motorola sold it's first car radio on June 23, 1930 to H.C.Wall of

Fort Wayne, Indiana for $130.

Motorola made their last car radio in 1984.

|

|

Another early Motorola

car radio. Image: Jim's

Antique Radio Museum

|

|

|

Retail promotional

display for the Motorola car radio, 1930s, Image: This

Day In Tech History

|

But while the American AM radio band before the North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement (NARBA) legally ran from 550-1500 kHz, the lower police band was still tunable on most ordinary radios and some early radio dials ran as high as 1800 kHz. That created a problem with criminals getting advance warning by eavesdropping on police reports on higher tuning (or modified as such) radios. Not to mention nighttime skywave interference from other police department radio systems. So by 1932, all police radio communication started to be moved up to higher (and higher), shorter-range bands, FM transmission and eventually, digital encryption. The lower frequencies were also used for early TV experiments.

|

|

1941 Motorola 2-Way

Radio. Image: Geoff

Fors/WB6NVH.com

|

|

|

Image: Geoff

Fors/WB6NVH.com

|

And the lower frequency police band of 1500-1600 kHz was also established in 1932 as an experimental High Fidelity radio band. The most famous station in this band was W2XR 1550 AM New York, which became WQXR, a legendary New York City classical music station. NARBA officially incorporated 1500-1600 kHz into the standard AM radio band. A later expansion in the 1980s added 1600-1700 kHz in the AM radio band

But radios didn't become standard equipment in cars until after World War II. In fact, very few auto manufacturers offered radios and only in selected models. Car radios were still considered a novelty to them in spite of the growing number of after-market manufacturers, including Philco and Delco,

|

| 1951 dealer promotion display for the Motorola Volumatic Car Radio. Image: eBay |

Nearly all car radios were AM only. AM was the dominant radio band and would be until 1975. FM radio in the 1950s at this time was rare in the home and even rarer in cars. And second, FM radio signals at the time were quiet and uncompressed. While AM signals remained fairly steady driving over hills and around buildings, FM in motion was subject to the "picket fencing" effect, the "fwip-fwip-fwip" sound an FM radio makes in motion.) Because of this, FM was thought as useless for cars by most mainstream radio manufacturers. But this didn't prevent upstart innovators from trying.

|

|

The Gonset 3311 FM

Automobile Radio Tuner was the first FM car radio converter. These

converters mounted under the dash and used a tiny built-in AM

transmitter tunable on a couple of pre-set frequencies to rebroadcast the FM signal to the car's AM radio.

FM radio converters like this were available until the early 1980s.

Image: Somerset

|

|

| Image: Somerset |

|

| Image: Somerset |

|

| Image: Somerset |

High Fidelity became a national craze in the 1950s. And experimentation spilled over to automobiles. But until 1956, it was only radios. You still couldn't play your own recorded music in your car.

Enter the Chrysler Highway Hi-Fi.

The Highway Hi-Fi was an option for newer Chrysler cars from 1956 to 1960. They played special 7" records that played at 16 2/3 RPM, half the speed of a standard LP. The 16 RPM speed also became featured on many home record changers, allowing these records to be played in the car or at home.

The benefit of a slower speed was it allowed for longer play on small convenient records. And the stylus and tone arm of the player was less susceptible to skipping around the grooves from vibrations of the car. The tone arms of the players were also very heavy, which lead to a record wear problem.

There were also only 42 titles, all of them back catalog material of Columbia Records. The discs were made by the Special Products division of Columbia for Chrysler. There were no other record companies that made records that were compatible with the Highway Hi-Fi.

Chrysler dropped the 16 RPM Highway Hi-Fi in 1960 and quickly reinvented the Highway Hi-Fi in the early 1960s as an after-market system using RCA's 45 RPM records in a changer. While this allowed for broader selection as nearly all record companies made 45 RPM records, the record wear problem and skipping in the grooves from vehicle vibrations remained. And ultimately, RCA gave up on the system.

But auto manufacturers didn't give up on the concept of car audio. In fact, their attention merely shifted to endless-loop cartridge tape systems such as the 4 Track tape player.

The endless loop tape cartridge was invented in 1952. It had many potential uses, but radio stations adopted the endless loop cartridge before anyone.

The benefit of "carts", as they were known was it prevented record wear (a major problem in the early days of Top 40 radio) With a song, jingle or commercial on each cartridge, they could be erased and reused as songs that either stalled or fell off the charts were replaced by breaking new hits. Or as jingles and commercials were updated. It made on-air radio production much simpler when using highly repeated material.

Toledo businessman Earl Muntz saw a potential for car audio use in these broadcast tapes and went into business making 4-Track tape cartridges and players for car use in 1962, later adding home units as well.

William Lear, who helped develop the first Motorola radio was riding high on success. He invented the Lear Jet in 1963, a private luxury aircraft for wealthy business people and owning a Lear jet was the ultimate status symbol. Lear was in a car with Muntz and listening to the car's 4-Track system when he had an idea. While the 4-Track tape was suitable for single albums, many classical albums were double albums. But by narrowing the tracks to 8 tracks with four stereo programs, he could put a double album on one tape cartridge and efficiently save recording tape (which was still selling for premium prices in those days.) for single albums.

Lear began developing the system in the late 1963 and unveiled the Stereo 8, as the format was originally called in 1964. The biggest difference in the design of the 8-Track tape from the 4-Track was the pinch roller was part of the cartridge itself in the 8-Track. This helped to protect the tape.

And not only that, Lear had very high connections

with the Ford Motor Company and RCA Records, who had enough faith in

Lear to manufacture auto players and pre-recorded tapes for this new

system. Needless to say, Lear's 8-Track quickly began to dominate

over Muntz's 4-Track in the consumer marketplace.

But Muntz ultimately had the last laugh. I recently discovered Muntz analog technology went away a lot later than I had previously known. Radio stations of course still depended on it through the '70s, '80s and in the 1990s, when digital began to take over radio station control rooms, it morphed into something new for the late '90s - the gigantic Muzak Background Music tape of the 1990s.

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about the first Muntz 4-Track stereo tape players of 1962 was they were built to last. And they could even play the 1990s cartridges because it used the same technology. Just in a massive form that they had planned for decades in advance.

|

|

A super rare 1960s Muntz Home Stereo 4-Track Tape

Player, similar to the one in the above video with original wood

case. Original Muntz Car Stereo 4-Track Tape Players could play the

giant Muzak cartridges of the 1990s too. Images: eBay

|

The 8-Track reigned car audio for most of the '70s.

But cassette tape was starting to make inroads. By 1980, cassettes

had overtaken 8-Tracks as the most popular car tape format.

|

| Remember these? |

Radio was still the most popular medium in cars. But

radio was also changing. FM was replacing AM as the preferred band

for music, leading more auto manufacturers to include AM/FM radio as

standard equipment as opposed to AM alone. The stations themselves

began using more compression and became louder. This had the effect

of masking minor picket-fencing noises and the overall generally

crappy factory car stereo speakers, improving FM's sound in vehicles.

Even low end portable radios sounded better.

KUBE

93.3 FM Seattle was a prime example of manic

compression. It

really did sound like this. In the 1980's to early '90s, KUBE was the

LOUDEST station on the Seattle FM radio dial - bar

none. And they were

extremely successful. They literally jumped off the dial when you

tuned past them and there was no questioning what you were listening

to. The station had jingles

galore to drill

that

in your head.

AM radio stations however was starting to struggle. Music formats

became older-skewing or stations flipped to talk radio. With

exception of the rare Top 40, alternative rock or hard rock station,

nearly all AM pop stations became oldies. Country music had largely

moved to FM and the question was (and still is), will AM radio

survive?

Enter AM Stereo. It was designed to give AM a competitive advantage to FM and AM Stereo really did sound good. But there was no standard amongst broadcasters or radio manufacturers on which transmission system to use. This caused listener/station and manufacturer confusion and ultimately the idea never took off.

Besides, the public's attention had turned towards the CD. The Compact Disc was invented in 1979 by a joint project of Sony and Phillips researchers and first sold in Japan in 1982.

It was designed as a rich audiophile toy because

nearly all of the very first CD titles were classical. The CDs

themselves costed $30 each in 1984 (that's $70 in 2016 dollars.) Pop

music also began appearing on CDs that year and so were the first

in-dash CD player prototypes.

But it would take until 1987 before the CD was on

nearly the footing as cassettes and the then fading vinyl LP. Sony

had invented the battery powered Discman in 1985 for playing CDs.

And soon, adapters to play the Discman and other

battery operated portable CD players through existing car cassette

players were made.

But car CD players didn't become standard until the

early 1990s. And soon, they would be upended by the MP3. But there

were usually no adapter inputs for MP3 players. This led to the

creation of tiny FM transmitters that relayed the audio from the

headphone jack of an iPod or any other headphone jack equipped medium

to the car's FM radio.

And radio was undergoing enormous changes as well. AM radio continued it's decline. But it was the effects of The Telecommunications Act of 1996 that changed the landscape of radio. Soon, hundreds of once independently operated radio stations or those owned by smaller chains were gobbled up by mega-conglomerates such as Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia), CBS, Cumulus and Entercom. Programs, air personalities, formats and even entire stations that were once local institutions were suddenly scrapped as stations bought their rivals and changed the formats and radio listeners began to not like some of these new changes. There were demands to create a low power FM (LPFM) service. And the rise of satellite radio led the terrestrial radio conglomerates to respond with HD Radio.

HD Radio (Hybrid Digital, not High Definition) worked

by piggybacking a digital signal on the main analog radio signal.

Each digital signal could hold up to 4 channels of different

programming. The HD-1 channel is always used as a digital simulcast

of the main analog signal and HD-2, HD-3 and HD-4 channels were used

for alternate programming or leased out to radio networks or

community/ethnic groups. But the HD Radio sub-channel programming was

lackluster at best and few station clusters could keep up with the

demands of not just their main signals, but all their HD

sub-channels. And listeners reaction to HD Radio was tepid at best.

Because that was all that was on HD Radio, just the usual stations

and these strange jukeboxes and talk programs on the HD

sub-channels.

But soon, HD Radio became standard in newer cars and

after-market car stereos. Ten years after it's launch, most radio

listeners who purchase newer cars are slowly becoming familiar with

HD Radio, if still mystified by the alternate programming and system

features. The FCC also ruled that radio stations may feed analog FM

translator stations an HD-2/3/4 sub-channel signal, creating little

analog FM radio stations covering a vastly smaller area than the main

signals (the maximum legal power of an FM radio translator is 250

watts. Tower height and nearby co-channel or adjacent channel

frequencies are also a factor in determining actual power.) Using

this loophole, that has ultimately become the main purpose of HD

Radio from the standpoint of the radio industry; To feed analog

radio.

Another major development came in 2005, when the FCC allowed AM radio stations to also operate FM translators, giving AM stations that could previously broadcast only during daytime hours the ability to broadcast 24 hours on FM as well as revitalizing local AM radio stations lucky enough to be in areas with enough available local FM radio bandwith to have them.

Using FM frequencies to relay their AM programming,

the purpose is to catch the listeners who could not listen to the AM

signals due to the particular signal anomalies of the AM station. Or

level of the local noise floor of the AM radio band in their areas.

Or most people would simply never be caught dead listening to AM

radio (usually the latter.) This led to many struggling AM stations

with dwindling oldies or talk formats with FM translators to switch

back to contemporary music formats, re-branding under their FM

translator frequencies. WGMP 1170 AM Montgomery, AL "104.9

The Gump" is an example of such a station.

Satellite radio was invented in the 1970s when radio

stations began using satellite delivered programming. In the 1980s,

many terrestrial radio stations rented a transponder on a satellite

to relay their programming to distant areas (CFMI Vancouver, BC used

the Anik-D satellite to relay it's programming.) And in 1990, there

were people envisioning a system that would be like cable, but for

your car where you could get hundreds of the best radio stations in

America for a low monthly price. Satellite CD Radio, Inc. petitioned

the FCC to assign new satellite frequencies to broadcast digital

audio to cars and homes

But the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) set their face against it. The NAB felt this would jeopardize local radio, but Satellite CD Radio, Inc. pushed on, They became CD Radio, Inc and spent the next five years lobbying the FCC to allow for a satellite radio service and another building capital for the launch of three satellites and became Sirius. The FCC also sold a license for satellite radio to American Mobile Radio Corporation. This company would become XM Satellite Radio.

Satellite radio would get it's biggest promotion yet from something completely unrelated to them. At the 2004 Super Bowl game, Janet Jackson experienced a "wardrobe malfunction" during a duet with Justin Timberlake, which exposed her right nipple for less than a split second. No one actually saw her nipple, but the pixelated video close-up of her right breast was replayed in slow motion on news programs over the course of several weeks. Which resulted in a massive (and obviously manufactured) uproar over obscenity in broadcast media.

Until Jackson's debacle, people had gotten used to

nationally syndicated "shock talk" personalities such as

Howard Stern and Tom Leykis on the radio. Suddenly even the vaguest

references to genitalia were suddenly off limits. This did not only

affect the shock talk shows, but the public service programs that

discussed serious topics as important as prostate and even breast

cancer.

Classic Rock radio stations which had previously

broadcast uncensored versions of "Jet Airliner" Steve

Miller Band, "Who Are You" The Who and "Play Guitar"

John Mellencamp for decades with no complaints whatsoever during

daytime hours were suddenly forced to play the clean edits of these

songs. Or stop playing them. Period. Within hours of the "Nipplegate"

incident, the FCC sent out strict, yet extremely vague obscenity warnings to

terrestrial radio/TV broadcasters with draconian fines and

repercussions for even the slightest violation, requiring hours of

legal consultations from station owners, managers, programmers and

personalities.

Even the lawyers weren't sure. Beyond child

pornography, there is no absolutely clear set definition of

obscenity. Just an extremely vague "three-prong" litmus

test. But your art may be someone else's smut. So the Supreme Court

in their ruling of FCC

v. Pacifica Foundation left it at seven deadly words you're not

supposed to say on the radio and the FCC to

determine if and when you can say them (they haven't exactly done

a terrific job.)

|

| The Seven Deadly Words You Can't Say On The Radio |

And there's still no truly uniform way to determine

what is indecent or profane either. Society changes with the times

and the broadcast standards of 1978 do not apply in an age when you

can hear the seven deadly words on any school playground.

And Howard Stern finally had it. He left terrestrial

radio and it's restrictions to join Sirius. Here's

an audio interview where Howard Stern directly confronts then FCC

chairman, Michael Powell on obscenity during Ronn Owen's show on KGO

Radio San Fransisco, October 27, 2004. Tom Leykis went to self

syndication. Others conformed to the tighter rules or went to

podcasting.

Sirius and XM merged on February 27, 2007. The FCC concluded it was not a monopoly as mobile streaming radio was being developed, ushering in services such as Pandora and Spotify as well as an almost infinite assortment of terrestrial, foreign and streaming-only broadcasters. The podcast is allowing listeners to control their own listening schedules.

And going into the future, it looks very likely streaming and on-demand radio will eventually replace AM/FM, satellite radio and all physical formats. As cars themselves become more dependent on web based artificial control and access, this is the only next logical step in the evolution of car audio. Terrestrial radio is just one of a bazillion different other entertainment apps of daily life. And mobile technology is quietly developing as we speak.

And as so will the model of car audio.